Understand a language(s) but not speak them or speak but only very little. Most learners might have experienced this somewhere in their learning journey. I am no different.

I’ve always been wondering about it for years and only found out the term for it a few months ago before writing this. It’s called receptive bilingualism and turns out it’s actually pretty common.

So, this will be about how I became a receptive learner and what caused it.

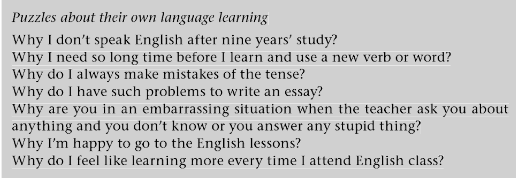

Take a look at this excerpt from Dick Allwright and Judith Hanks’s book called The Developing Language Learner: An Introduction to Exploratory Practice. Out of those 7 questions, how many do you often find yourself in that situation? I checked 5 of them. Number 4 indirectly leads me to write this.

Back in 2016, I wrote redefining the definition of fluency. Somewhere in the content, I mentioned 4 what-ifs questions. At that time, I didn’t know what it was called (the second what-ifs).

Again in 2015, I wrote about 4 methods to make language learning fun in the classroom and I mentioned how I went blank after being asked to write an essay.

This frustrates me not knowing what to do when the solution is right in front of me and I’ve been talking about it many times in my blog – Speak, speak, speak.

I’m well aware speaking is one of the most important skills. What I didn’t know is what it can cause if you put less effort into it.

I’m not talking about being okay with making mistakes and all that because that’s really obvious. I’m talking about being a receptive learner.

1- Memorize with zero understanding

Benny Lewis has made a bold post saying that studying will never help you speak a language. When I got into a school that actually had a few Arabic language subjects I was clueless because most of the students already knew that language and only very few had zero knowledge.

Even though the school did teach Arabic I was still as blank as the A4 paper.

I mean, how can I learn the language in a matter of weeks when other subjects are waiting for me beyond the beginner level?

It’s like you’re thrust into a foreign situation and you don’t know what to do but to adapt quickly. In my case, I chose to learn it by memorizing and not understanding.

I have to say it did help me pass the exams but not when communicating with people. Not that the latter really mattered at that time because even the teacher (2005) and the professor (2014) didn’t emphasize much on speaking skills.

Don’t you think that indirectly made us all a receptive learner?

When I was in high school, we had English oral exams. Now that I think about it, it’s funny how they expect us to pass when all they focused on was grammar.

I guess studying foreign languages at school is all about how to pass them academically and not how to pass and use them at your disposal (communicate with those who speak the language), at least that’s the situation where I attended.

Now, I understand that memorizing will only get you this far.

Listening is receptive while speaking is productive. They make use of your internal store of words, meanings, phrases and grammatical knowledge in very different ways. - Acutia

Let’s talk a bit about how it happens, scientifically. There are two areas in our brain called Wernicke and Broca.

The way I understand it is Wernicke is the area at the back of our brain that receives all the sentences and speeches whatsoever and comprehends the meaning. Broca is the front one where it constructs and produces the sentences.

In short, the latter part doesn’t do much work which resulted in me understanding but not speaking the target language.

To some extent, I agree with what Viviane Blais said, I am more of a passive speaker than an active speaker. As much as I would love to have conversations with Spanish native speakers every day, time and situation just don’t allow it.

2- Speaking is tiring, listening is easy

In most cases, it’s the meaning of sentences that we try to understand, rather than the individual meaning of every single word in the sentence. – scienceabc.com

The way I learn English is I translating from word to word. It works most of the time. Yes, even when I speak. I can’t say the same for Spanish and other languages though. The thing with speaking is I have to think fast.

To come up and construct with the words myself is very challenging. This is where the ah, oh, uhm and well come a lot. I guess at some points I’m just tired of it and resort to just getting used to listening and reading because the sentences are already there. You just have to figure out what they mean.

Somehow, I don’t want to acknowledge that I’m tired so I make ‘trying to get my ears familiar with the language’ as an excuse. Yeah, we all have made such an excuse, right?

Speaking a language requires you to remember grammar rules and if no one teaches them to you it is far easier to remember a few words than rules.

I learned a lot from the video above. The 3 symptoms of the brain shutting down she talked about are spot on.

Sometimes, I focus more on myself than the one I speak to. I focus on how I can deliver what I want to say so the other person can easily understand. It depends on who they are.

If he/ she speaks English well then, I have to make sure my sentence is grammatically correct which can be a bit of pressure. If he/ she doesn’t then, broken English is fine.

I’d like to quote a piece of advice from Marianna Pascal about English (I think it can be applied to other languages as well).

It’s not an art to be mastered. It’s just a tool to use to get a result.

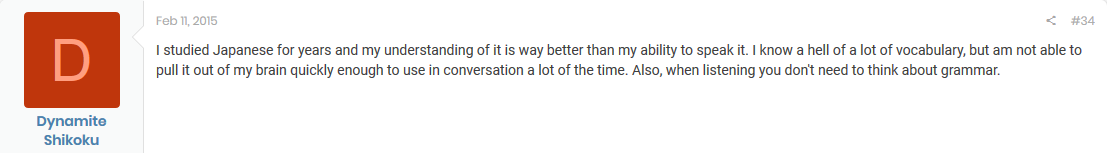

Thank you, Shikoku! At least, I’m not alone in this battle. I’ve been self-teaching myself Spanish for 5 years already and I understand better when I listen. What’s wrong with me?

Receptive Bilingualism – The Advantage

It is possible to understand another language without actually having learned it. Whether by listening or by reading, a person can use similarities in vocabulary, contextual knowledge (understanding of the topic or situation), and various other mental strategies to guess part or all of the meaning. - Anne W Zahra

I couldn’t agree more with Anne. Personally, I think people who learn more than 2 languages but aren’t fluent yet have many benefits. One of them is being able to understand a language(s) they haven’t learned.

All this could happen if they come from the same family. It's also possible with different language families.

For example, my native language is Malay and Arabic. Malay borrowed quite a lot of Arabic words and because of that (and the fact that I’m Muslim), I can understand Arabic a little bit.

The same with Tagalog. It’s similar to Spanish but they don’t come from the same family though Spanish had some influence on it (correct me if I’m wrong). There are also a few words that are similar to Malay.

There is one problem in these situations and that is false friends. It’s where the spelling and/or sound are similar but the meaning is different. You can easily misidentify the meaning.

If you think your translation doesn’t make any sense, it probably is. Check again with Google Translate or your language exchange friends.

There are a few websites where you can test your knowledge of the world’s languages and see how many you got right. No, you don’t have to write or anything just listen to the audio and guess which languages are they from.

Here’s to name a few; Name That Language, Ling Your Language, and Language Squad.

I like how Breckin Duckles compares this problem to grammar and vocabulary. In a way, it’s similar.

If we prioritize one over the other, we only complete half the skills and it will lead to a problem which in the end will be the ability to talk and have conversations with whoever speaks the target language.

Isn’t that the main goal of learning a language in the first place?

Anyway, I don’t want to end this writing with a negative vibe. I just want to say you should enjoy your learning progress. Don’t feel bad that your listening skills have developed much better than the others.

You’ve got to acknowledge listening is a skill, too.

Have you experienced being a receptive learner? Or are you currently a receptive learner? How does it happen? Share it with us in the comment below.

Satsmoona says:

Interesting post, thank you for sharing. I have experienced receptive bilingualism myself, and one way to overcome it is by practising communicating in the target language alone. However, not using both languages at the same time, I have noticed that over time I am becoming more active in the target language and passive in my original language, which makes interpreting a challenge despite being fluent in both. Without the scientific backup, I’m tempted to say that a well developed Broca’s area is what helps with this mental gymnastics that is interpreting. But that’s a topic for another post.

Meina says:

Hi, Satsmoona. Thank you for sharing the tip. That’s literally my goal which is to force myself to speak more Spanish. My Broca definitely needs to work harder this year. What’s the second language you speak? At what point did you realize you’re becoming more active in the target language?

Satsmoona says:

I also speak French, and it is when I speak it that I realise how ‘unFrenchie’ I have become. Basically, I have started using tiny automatic English responses, such as ‘well’, ‘so’ etc. in every sentence. And I sometimes dream in English too! I hope this answers your curiosity, and all the best with your language learning… it is worth the effort!

Konverta ( LingualAddictJa ) says:

nICE THIS WAS VERY IMFORMATIVE AND IT’LL CINTRIBUE TO A CONCEPT I WANNA WORK ON IN THE NEAR FUTURE.

Meina says:

¡Hola Konverta! Thanks and I’m glad it helps.

John M says:

I am a polyglot to some extent…having learned sizeable parts of quite a few languages, including Spanish, French, German, briefly looked at sanskrit, and Latin…and this was all from my freshman year of high school. Add to that the Irish Gaelic that I learned from my parents (I’m first generation American). As an adult, I attempted Esperanto, but became bored after 74 days (or so Duolingo told me).

But when I looked at Interlingue for the first time, I was shocked by how much I could read and understand. My reading comprehension is that of a fluent native speaker, but I can not speak it to save my life. I can not call it up fast enough to speak more than a few basic sentences…but I am onto my 5th book- cover to cover. And I am satisfied with that. I don’t intend on speaking face to face with someone using Interlingue, but I enjoy reading it nonetheless.

Meina says:

Hi, John. I guess that’s what happened when you’ve been learning quite a few languages. How difficult is Esperanto? By the way, thanks for sharing!

John M says:

Hi Meina.

Well, Esperanto for the most part isn’t difficult, as it stands. However, some of the words appear to be purely invented (no derivation from other languages). Interlingue makes perfect sense to me because of 2 simple facts: 38% of the words are English, or based on English, and the other largest contingent of words are from romance languages. Overall, it makes for a quite rewarding language learning experience.

Meina says:

Thanks for the explanation. Sounds interesting! I may learn it someday.